Credit: ThinkStock

As documented in Thomas Wolfe's dare-I-say epic novel—The Right Stuff—astronauts have historically been imbued with the public adoration of a demigod, existing somewhere between war hero, Olympian and Hollywood heartthrob. The majority of astronauts—and every one depicted in Wolfe's novel—have also been men. (The first woman to go into space—astrophysicist Dr. Sally Ride—didn't get suited up until 1983, though NASA was founded in 1958. To this day, women only represent 26% of NASA's astronaut corps.)

Their wives, while equally showcased and exalted as the familial linchpin and loving partner, privately suffered at the hands of their husbands' extramarital affairs, general megalomania and more-than-possible death.

NASA, in trying to drum up support, money and public fascination with their space program, ran a tight and well-oiled PR juggernaut, even partnering with Life magazine to tell the behind-the-scenes stories of the astronauts and their private lives.

As Mary Roach describes in her book, Packing For Mars:

"...the whole era was very stage-managed. The wives became a publicity tool for NASA. They had a contract with Life magazine and basically had to be happy and smiley and serve cookies, but really, on the inside, they were like, ‘Fuck you! You’ve been gone for six months, and I haven’t seen you, and now you’re back and doing ticker-tape parades, and people think you’re a hero, but you don’t care about your kids, and you’re fucking everything that walks, and I still have to be on television smiling in my Pucci outfit.”

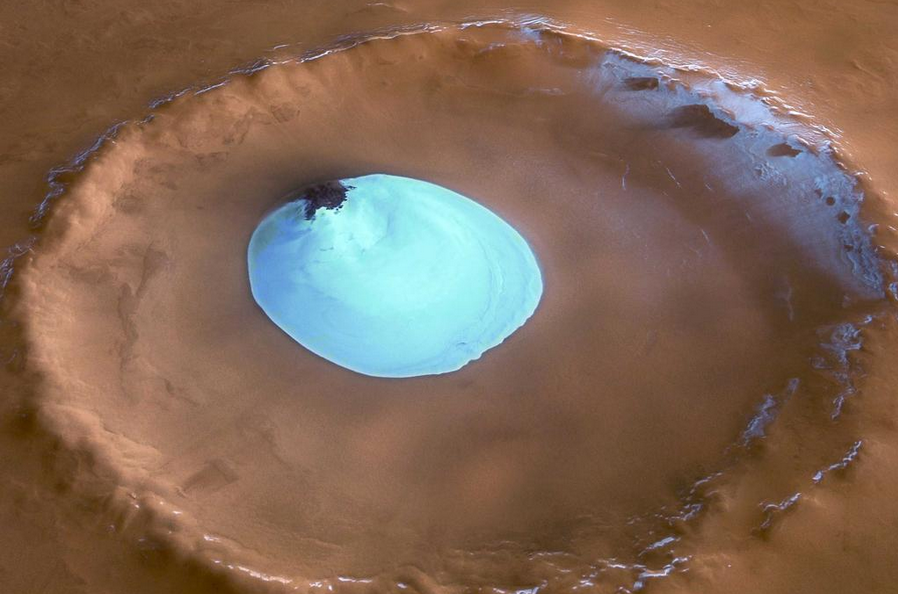

Since the dawn of NASA, the space program to visit one planet in particular—the mighty red planet of Mars—has been plagued by more than a few gaffes and obstacles, from the $193 million disintegration of the Mars Climate Orbitor to the supposed crash of the Mars Polar Lander in 1999 (cost: $110 million). After these and other disasters, the frenzied, hell-yeah patriotism that accompanied the Space Race dissipated; in its wake, we were left with a creeping feeling that while the government was driving some robots around and capturing some breathtaking photography . . . humans were decidedly slipping from the radar. Would we ever step foot on Mars? Or establish an alternative society forged on its fiery crust?

Enter Professor Scott Hubbard. In the 1990s, he launched Lunar Prospector, a decidedly successful mission that discovered the first signs of water on the Moon's surface. He also established the Astrobiology Institute, which to this day focuses on coordinating the efforts of scientists worldwide to explore the possibility of life on distant planets.

If anyone could help NASA emerge from their general morass of failure and American anemia, it was Hubbard.

Mars Man

In 2000, Hubbard was formally asked to join NASA as its first Mars program director, tasked with restructuring the entire exploration program. "That vision was characterized as ‘follow the water’ and has become the central theme of the initial exploration,” Hubbard says in his book, Exploring Mars: Chronicles from a Decade of Discovery.

Under his watchful eye, Hubbard has managed to launch six successful missions to Mars, including the Mars Reconnaissance, which returned 26 terabits of data, more than all the other Mars missions combined; his latest mission, Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution, launched in 2013 and is currently en route to our little red neighbor.

Currently, Hubbard is manning Mars at NASA, is a consulting professor in the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics at Stanford University, serves as the director of the Stanford Center of Excellence for Commercial Space Transportation, is the editor-in-chief of a new peer-reviewed journal called New Space that's devoted to the emerging entrepreneurial space industry, holds a spot on the SpaceX Advisory Panel and is the Sentinel Program Architect at the B612 Foundation, which—seriously—is dedicated to protecting the Earth from asteroid strikes.

He's pretty much the most unassuming badass you've ever laid your eyes on.

Other Mars Movers And Shakers

Working alongside Hubbard's efforts both literally and—at times—metaphysically is SpaceX. Founded by tech-giant Elon Musk, it is currently vying for a spot in NASA's astronaut taxi (commercial crew) competition. Meanwhile, over at Mission-One Mars (a nonprofit dedicated to establishing a permanent human colony on Mars), they just announced a Ticket to Ride contest, which offers contestants five entries to win a (round-trip) journey to space for every $1 they donate to the pending mission. They plan on winnowing down their 705 candidates to just two men and two women for their one-way trip in 2018.

Hubbard just returned from a conference appropriately named "Humans In Space" as part of the European Rover Challenge in Poland, which asks eggheads to "design, construct and operate a rover that will that will most successfully complete a number of Mars-exploration themed tasks designed by the organizers . . . "

In addition to fostering badass robots, what exactly does a seminar schedule for astrophysicists offer? So glad you asked.

In addition to the run-of-the-mill offerings like “Adaptive vision system for extraterrestrial exploration,” you could have also checked out "How to get specialist medical treatment in space? The issue of tumour diagnostics and how digital pathology can help"; "Subsurface autonomous operations on planetary bodies: challenges and opportunities"; “Human Trace Project—sending art to Mars”; and “Legal aspects of space business: now and tomorrow.”

“I will also take a look ahead at the next decade, the plans for a Mars Sample Return campaign including Mars 2020 and the growing consensus that sending humans to Mars around 2033 should be the single organizing principle of future space exploration. In addition I will outline the technical, fiscal and institutional issues that must be overcome.” —Hubbard, Astrowatch.net

What did you do at your job today?